When Jean and Jeanne Baret had their daughter they did the obvious and named her Jeanne. From a family of day laborers in the fields of Burgundy, France, she was destined to be poor and never venture farther than 20 miles away. But Baret’s love of plants was her ticket to a worldly adventure that was at times more challenging than the life she left behind.

Baret came from a mixed family: her father was Catholic and her mother was Protestant. Protestants tended to be more literate having learned to read the Bible on their own, and Baret’s mom taught her how to read. Perhaps the freedom and ability to learn about the world also instilled in the young girl the curiosity and desire to discover more about it.

Baret’s broader education took place in the fields where she played. She became an expert in the medical properties of plants. As an “herb woman” she supplied druggists, physicians, dentists and veterinarians. One day when she was picking and analyzing in the fields she met her future.

MEETING MR. RIGHT Philibert Commerson was born near Lyon, France 12 years before Baret. He appeased his father by studying law and medicine and then followed his heart and became a botanist, at the risk of losing his inheritance. When he was 26 years old, this passion led him to explore and collect samples in the fields not far from Baret’s home where they had a fateful encounter.

Commerson was married to a rich heiress, but he spent a lot of time with Baret learning about the curative properties of the local flora. When his wife died giving birth to their only child, Baret became more integrated in his life. She moved into his house and assumed the duties of nanny, household manager, lover and assistant.

Baret became pregnant when she was 24 years old, which complicated their lives. For Commerson marriage was not an option, so the couple had to deal with the fact that their lifestyle was unacceptable. The best solution seemed to be to move away. With the money Commerson inherited from his wife, they turned the need to escape the condemnation of their neighbors into an opportunity to broaden their horizons.

Commerson and Baret each did something to help facilitate a clean break. It was mandatory for an unwed mother to have a certificate of pregnancy which named the father. However, somehow Baret was able to make the appropriate connection which allowed her to decline to state who fathered her child, and she gave him her last name. Commerson gave his two year old son to his brother-in-law, a priest, to raise. The couple went to Paris to create a new life for themselves.

In December 1764 Jean-Pierre Baret was born. Commerson, having already proven he did not have much paternal instinct, hated the inconvenience of having a newborn around. Apparently Baret’s maternal instincts were not very strong either, and one month later she abandoned her baby at the Paris foundling hospital which then turned him over to a foster mother. Less than one year later Baret received news that her son had died.

In a way, Baret had been relieved of one burden, but another one manifested. Commerson had pleurisy. Baret became the caregiver of her lover and his collection of plants. As he healed he was able to write a book, but he continued to look for the perfect project that would really put his name on the map.

RUNNING AWAY TOGETHER Britain, the Netherlands and Spain had already sailed around the world, and France wanted to get in the game. The goal was to find a land mass in the southern hemisphere. An expedition was planned, and Commerson was selected to be the naturalist on board who would discover and collect unknown species of flora and fauna. It was the perfect opportunity for Commerson, but not for Baret. Women were not allowed on French naval ships, but the couple came up with a solution: dress Baret as a man and have her work as the naturalist’s assistant since she had the experience to be convincing. To facilitate the ruse, she started using the masculine spelling of her name, Jean.

The frigate La Boudeuse, under the command of Louis-Antoine de Bougainville, and the supply ship L’Etoile, with captain Francois Chenard de la Giraudais at the helm, set sail together on February 1, 1767. Commerson and his assistant were on the Etoile. Baret disguised her gender by wrapping her chest with linen bandages, so tight that she had trouble taking a deep breath, and wearing men’s clothing. It was her job to carry onboard her boss’s bags and most of the extensive field equipment they brought along. When captain La Giraudais saw how much they had, he knew it would not all fit in the small berth they had been assigned. He offered the scientist and his assistant the 30 x 15 foot captain’s cabin.

Suspicions about Baret’s gender were aroused immediately. It was very unusual for a servant to sleep in the same cabin as his master, and Baret was never seen relieving herself at the “head,” holes cut out of the protruding part of the forward deck. Such a breach of regulations could ruin La Giraudais’ career, so he ordered Baret to sleep with the other servants. She did not feel safe in that environment, so she slept with one of Commerson’s loaded pistols and threatened to use it one evening when she was maliciously approached by some curious men.

La Giraudais called Baret in for questioning, and she explained her situation by claiming to be a eunuch who had supervised a sultan’s harem in the Ottoman Empire. While the captain may not have been totally convinced, it was good enough to be allowed back in Commerson’s cabin. In addition, a previous dog bite in Commerson’s leg had become ulcerated. The infirmity was another justification to allow her to reside in the master’s cabin so she could tend to his needs.

Baret’s life on the ship was not easy. Living in such close quarters with Commerson made him quite moody. The temperature was consistently in the 80s, and the sweat-soaked linen wrap chaffed at her skin giving her eczema. They were both living for the day when they could get off the ship.

The first opportunity to disembark was a brief stop in Montevideo, Uruguay before heading up the eastern coast of South America to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. In mid July, five months after leaving France, the naturalists were able to go ashore and start the work they were commissioned to do.

DOING A MAN’S JOB The sores on Commerson’s leg were turning into gangrene. Baret’s treatments prevented amputation, but Commerson’s mobility was severely restricted. He was able to take the rowboat but he was in no condition to wander around collecting plant samples. It was up to Baret to do all the physical work. She carried the food for the day, the wooden presses for preserving samples and all the field equipment which included a spade, glass vials for seeds, tiny boxes for insects, magnifying glasses, a telescope, a compass and a butterfly net. Commerson lightly referred to Baret as his “beast of burden.”

The most well known discovery Baret made was a colorful vine native to South America. Commerson respectfully named it after Commander Bougainville: Bougainvillea brasiliensis, or what we call bougainvillea.

The Boudeuse and the Etoile continued their tandem journey back down the coast of South America where they spent 38 days feeling their way through the perilous maze of the Strait of Magellan. There were no charts for navigation since this was the first time French ships were in the region. They stopped in Patagonia and started across the Pacific Ocean at the end of January 1768. Whenever they stopped, Baret and Commerson went botanizing.

COMING OUT OF THE CLOSET If Baret’s gender had been a secret up to that point, that changed when they hit Tahiti. A native Tahitian named Aotourou, with previous experience with foreign ships, came onboard the Etoile. He saw Baret standing with several other crew members, pointed to her and identified her as a girl. Undoubtedly confused by the accuracy of the observation and visibly angry at being outed, she ran into her cabin. Aotourou, unaware that he had said anything wrong, offered an explanation. In his culture it was very common for some men to dress like and perform the duties of women (called mahu). In fact, they held a respected place in the society as having the best qualities of men and women. Aotourou believed Baret to be a mahu, someone who dressed and acted like a person of the opposite sex, with a specific purpose on the crew. Now that Baret’s identity was revealed, she was afraid of being attacked and carried a pistol with her whenever she left the cabin.

After leaving Tahiti in April 1768, the conditions of the trip got progressively worse. They sailed for three months without being able to find a suitable port. They used up all the fresh water, and the cases of scurvy increased daily. They couldn’t seem to catch any fish and had to resort to eating the rats onboard. When they finally landed on the island of New Ireland (part of Papua New Guinea) Baret had a few days of successful collecting before her life became a nightmare.

Each day Baret went botanizing, accompanied by a pistol to protect herself from her fellow crew members more than the natives. Several days after their arrival Baret joined the other servants who were doing laundry. They had been plotting to confirm Baret’s sex for themselves, and she unwittingly gave them the opportunity they were waiting for. They stole her gun and proceeded to rape her. In relating the incident in his journal, the ship’s doctor justified the actions of the men by conveying the benefit to Baret: she no longer had to bind herself to hide her identity. Back on board, Commerson feigned surprise at the news that Baret was a woman in order to protect his job. For the rest of the journey, Baret secluded herself in their cabin.

After leaving New Ireland, the explorers traveled for six weeks without any real food, and starvation was a constant threat until they could get provisions on the Dutch island of Buru. This posed a problem especially for Baret because she was pregnant.

In early November 1768 the expedition landed on the island of Mauritius, near Madagascar. Commerson had known the civil administrator from Paris, and he invited the couple to stay in his home at Port Louis. Baret was given her own room in the servants’ quarters, and she had some privacy for the first time in almost two years. When the Etoile and Boudeuse headed back to France about a month later, Baret and Commerson stayed on the island.

When it came time to deliver the baby, Baret and Commerson went to a plantation in Flacq in the northern part of the island and stayed with a Mr. Bezac. The new mom didn’t feel any more affection for this child than she had for her first one, and she left him to live with Bezac.

Baret and Commerson went to Madagascar for four months and collected 500 species of flora and fauna. When they returned to Mauritius they had to find a new place to live. They rented a house and lived together as a couple for the first time since leaving Paris. The contentment of this arrangement did not last long, however, because Commerson was diagnosed with rheumatism and then dysentery. Bezac welcomed them again in Flacq where Commerson died in 1773.

GOING HOME Baret was ready to return to France, but she had no money and no place to live until she could get some. She said goodbye to her son again and moved back down to Port Louis. She worked as an herb woman and barmaid for survival. While she was serving drinks she met a French soldier, Jean Dubernat, on his way back to France after serving in one of the colonies. Whether it was for love or convenience we can’t be sure, but Baret and Dubernat were married on May, 1774. Presumably to give herself a fresh start in life, the bride signed her name with a new spelling: Barret.

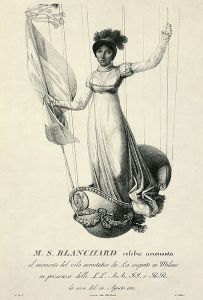

When Baret landed on French soil near the end of 1774, she became the first woman to circumnavigate the globe. But unlike the arrival of Bougainville and the crews of the two naval vessels five years earlier, there was no ceremony or recognition of her achievement.

The new couple set up house in Dubernat’s home town of Saint-Aulaye. Commerson had provided for Baret before they left Paris, leaving 600 livres to her in his will which she collected when she returned to France. That was about six times the annual wage of a servant. She finally had the means to buy a house and give her life some stability.

Baret did receive recognition for her contribution to society as a naturalist. Nine years later, the Ministry of Marine granted her a pension of 200 livres a year. On August 5, 1807, at age sixty-seven, Baret died. She left behind a legacy of plants, seeds, shells and insects that are housed in the Museum national d’histoire naturelle, giving future generations insight into the world around them.

QUESTION: What would you like to be remembered for accomplishing when you die?

©2011 Debbie Foulkes All Rights Reserved

Sources:

Ridley, Glynis, The Discovery of Jeanne Baret, A Story of Science, The High Seas, and the First Woman to Circumnavigate the Globe. New York: Crown Publishers, 2010.