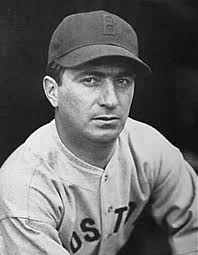

Moe Berg became famous for what he did, but it was his charisma and storytelling that endeared him to his friends. Below the surface he was very private, however, and the mystery that surrounded him facilitated a career change from being a public figure as a major league baseball player to the anonymity of being a spy.

Bernard Berg was lured to the land of opportunity around the turn of the 20th century. He ran a laundry, and while he ironed shirts taught himself to read English, French and German in addition to the Yiddish, Hebrew and Russian he already knew. He took night classes at the New York College of Pharmacy and moved his family to Newark, New Jersey to open his own pharmacy. Bernard and Rose had three children. Sam became a doctor, and Ethel was a lovely lady. Morris (Moe) had his father’s intelligence and curiosity, but not his ambition. For all his fame, his career choices made him a big disappointment to his dad.

When Moe was three and a half he insisted on going to school like his older siblings. He was an excellent student, and the only negative comment he received on an early report card said that he sang off key. Berg’s hobby was baseball, and he played street ball with the neighbor kids until he could be on a real team in high school.

Berg was voted the “Brightest Boy” in the class at Barringer High School, a private school where he was virtually the only Jew. He didn’t experience much anti-Semitism, but when Berg was recruited to play third base on the Roseville Methodist Episcopal Church team, he used the pseudonym Runt Wolfe and found it easy to pretend being somebody else.

After two semesters at NYU, Berg was accepted to Princeton where he played short stop. His arm and quick agility made up for being a mediocre hitter. He inherited his father’s facility for languages and studied Latin, Greek, French, Spanish, Italian, German and Sanskrit, graduating magna cum laude. Off the diamond he tutored his teammates, and to confuse their opponents Berg and the second baseman yelled strategy in Latin.

TURNING A HOBBY INTO A CAREER After graduation, Berg was offered a teaching post at Princeton but opted to play for the Brooklyn Robins (later the Dodgers). He got a $5,000 signing bonus for joining the team. After the first season he studied at the Sorbonne in Paris, taking history, linguistics and literature classes in French and Italian.

One reason Berg was able to accomplish so much was that he was basically a loner. He socialized but maintained an aura of mystery by not sharing personal information with friends. He hated accountability and disappeared frequently so that friends and colleagues rarely knew where he was.

When he returned from Paris, Berg was traded to the Minneapolis Millers, an American Association team, and then the Reading Keystones in Pennsylvania. He had already established a double identity for himself, and after the 1925 season he started planning for his post-baseball life by enrolling in Columbia Law School. He was traded to the Chicago White Sox and skipped spring training so he could finish classes. That did not endear him to the coaches, but when Berg’s professor discovered that he was the Berg who played baseball at Princeton, he arranged classes so Berg’s schedule could accommodate both his job and his studies.

Good thing, because during the 1927 season Berg pulled his team out of a dire situation. Within two weeks, the White Sox lost three catchers to injury. Even though he hadn’t played behind the plate since the sandlot days, Berg volunteered for the position. In his first game as the starting catcher, the White Sox beat the Yankees, and Babe Ruth was hitless. He played catcher for the rest of his career.

A REAL SINGULAR SENSATION In his whole academic career, Berg failed only one course, evidence. That prevented him from graduating from law school with his class. He was able to retake the course, and received his degree in February 1930. He passed the New York bar that spring and headed right off to spring training.

In early April, Berg injured his knee but was back in the lineup in May, although he only played 20 games all season. In the fall he joined the Wall Street law firm of Satterlee and Canfield, a job that justified his education and appeased his father but wasn’t as fun. He only worked during the off season and lasted there just a few years. In 1931 Berg was picked up the by Cleveland Indians, but bronchial pneumonia kept him in the dugout most of the season. The Indians released him in January 1932, and he went to spring training for the Washington Senators.

Being “the brainiest guy in baseball” opened up the opportunity for him to be a guest panelist on the radio quiz show “Information Please.” That seeming contradiction in his personality was only one of the quirks that distinguished Berg. He was eccentric about his wardrobe and always dressed in a black suit and tie. Every morning he took the first of three daily baths, picked up newspapers from several major cities plus some in French, Spanish and Italian, and read as many as he could during breakfast at a local diner. He was adamant about reading every paper he bought regardless of how out of date, and piles of them covered every flat surface in his apartment or hotel room. Until he had read it, a newspaper was “alive,” and no one else was allowed to touch it. Once he read it, it became “dead,” and he would dispose of it. If anyone, for any reason, touched one if the “alive” journals, Berg considered it dead and refused to read it.

A NEW EXPERIENCE In 1932 and 1934 Berg was a part of delegations that went to Japan to coach college teams there. He was so captivated with the Japanese lifestyle that he slept on a tatami mat and traded his dark suit for a kimono, and he learned enough Japanese to be conversant.

During his second trip, Berg did something that opened up another career option later. He didn’t show up for the final exhibition game, claiming afterward to have been sick. Instead he donned his kimono, bought flowers and went to the hospital to visit the daughter of the US ambassador who had just given birth. Speaking Japanese, he got her room number, walked past her fifth-floor room, threw the flowers in the trash and took the elevator up to the seventh floor where he climbed some stairs to the bell tower. He reached into his kimono, pulled out a movie camera and documented military installations, shipyards, and industrial complexes around Tokyo.

While he was gone, Berg was released from Cleveland, but the Boston Red Sox added him to their roster. He spent more time in the bullpen telling stories of his travels than behind the plate. He spent a few more seasons in a Red Sox jersey, but his days as a player were numbered. In 1940, the Sox put him on the coaching staff for $7,500 a year.

GOOD ENOUGH FOR GOVERNMENT WORK Becoming a coach was essentially being put out to pasture, and Berg was ready for something more challenging. As World War II escalated, the thrill of getting the clandestine footage in Tokyo nudged him toward more international opportunities. In January 1942, he retired from baseball and accepted an assignment from the Office of Inter-American Affairs (OIAA) to go to Latin America and monitor the overall health and fitness in the region for $22.22 a day.

His trip was delayed, but Berg was able to keep busy. William Donovan, head of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), forerunner to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), agreed to let Berg deliver an address directly to the Japanese people via short wave radio. Speaking in Japanese, Berg reminded them of the mutual friendship they had shared with America, especially through the common love of baseball. He encouraged them to denounce the political leadership that was leading them into committing national suicide.

Berg also took advantage of the postponement to find an audience for the film he shot in Tokyo. He screened it for key members of the intelligence community. The reaction to the footage was mixed, and the radio address had no real impact on the war, but both efforts proved Berg could handle clandestine work.

When he finally went to Latin America, his primary mission became to improve life for the US servicemen stationed there, something he thought was important. But he wanted more, so he made contacts, poked around and got some intelligence on the Nazis in Brazil. Washington liked his effort and tapped Berg for the OSS. While he waited for that appointment to come through, he was distracted by the first woman who was more than just arm candy.

Estella Huni was a tall brunette who played and taught piano. Like Berg, she was a voracious reader and spoke Italian, German and French. She introduced Berg to music, and he taught her about baseball. They lived together in New York, something respectable people didn’t do, and Berg’s father was so disapproving that he refused to meet his son’s girlfriend.

In early 1943 Berg officially joined the OSS for $3,800 a year. He learned all the skills a spy would need at training camp and passed his final by entering a heavily guarded American defense plant and stealing classified information. On May 4, 1944, Berg headed for Europe with $2000 in travel allowance, a .45 pistol and his black suits. His assignment was to find out which German and Italian scientists were working on an atomic bomb, and his primary person of interest was German scientist Werner Heisenberg, considered to be the greatest theoretical physicist in the world.

GOING UNDERCOVER Berg went wherever he wanted to go whenever he wanted and didn’t respond to orders to keep in touch with the OSS office. He maintained his established daily routine and translated any documents he acquired into English. He made contacts, and Paul Scherrer, the head of the physics department at a university in Zurich, Switzerland, led Berg to Heisenberg. Scherrer and Heisenberg were friends and colleagues before the war. Scherrer invited Heisenberg to Switzerland to give a lecture at the university, and attending would be Berg’s riskiest assignment.

Berg had studied physics, and he was briefed on what to listen for during the lecture. If he heard anything that indicated the Germans were on the verge of using an atomic bomb, Berg was ordered to kill Heisenberg on the spot.

Doing something like this was the reason Berg joined the OSS. On December 18, 1944, forty-two year old Berg dressed as a university student. In his pockets he had two things he hoped he wouldn’t have to use: a pistol to kill Heisenberg if necessary, and a potassium cyanide capsule to kill himself. He sat in the front row, and as he scanned the room, he realized that there were Nazi soldiers posted in various locations to keep an eye on Heisenberg. Berg took notes as Heisenberg expounded on theoretical physics, the content and language a little over Berg’s head.

Berg didn’t hear anything in the lecture that warranted him to take action. In talking with Scherrer afterward they agreed that Heisenberg was a German who was anti-Nazi. Berg’s approach shifted, and he wanted to bring Heisenberg to America to work. Scherrer thought that was a good idea and invited Berg to attend a dinner in Heisenberg’s honor where the scientist inadvertently confirmed the Allies wishful thinking. When someone baited him with the comment that he really had to admit the Germans were losing the war, Heisenberg admitted that was true. It was through Berg that the United States became confident that the Germans were not close to being able to detonate an atomic bomb.

The Heisenberg assignment was the highlight of Berg’s espionage career. After the war there wasn’t much for him to do. Berg resigned from the OSS in 1945 and became bored and restless. He was nominated for the Medal of Freedom, but he respectfully rejected the award, although he never explained why. It was hard to find something as interesting as being paid to roam the globe on secret missions for his country.

During the Cold War he was sent to Europe on a couple of assignments for the CIA to find out how far along the Soviet Union was to having atomic weapons. He got through a Russian checkpoint into Czechoslovakia (now the Czech Republic) by holding up a paper with a big red star on it. It was a piece of stationery from the Texaco oil company. He loved being back in the field, but he refused to be accountable for his time or keep records of his expenses. Berg hated bureaucracy, and that attitude wasn’t very compatible with government work. In 1954 his contract expired and his security clearance was revoked.

Berg ran into financial trouble when a company he had invested in went bankrupt. Adding in some unpaid personal taxes, the IRS claimed he owed over $12,000. Not willing to be beholden to anyone and with no income, Berg ignored the notice, refused to make payments and even refused to declare bankruptcy. Finally he made an offer to pay $1,500, and because Berg was a national hero, the IRS accepted. He had to borrow the money from a friend.

LIVING LIFE ON HIS TERMS During the latter part of his life, Berg depended completely on friends. He never married, and technically he lived with his brother and then his sister in Newark, but he was really a vagabond staying with friends wherever he happened to land. He carried his toothbrush and a list of phone numbers, and made friends with train conductors so he could ride for free. People loved having him around, and he was a very entertaining raconteur. He took advantage of their hospitality and often stayed for weeks. He spent hours reading, and it was not unusual to see him at the ballpark watching a game.

Berg was not without his own problems. In 1963 he started dressing very sloppily, and due to a large umbilical hernia, he no longer looked or acted like an athlete. He refused to have it treated until four years later when he met a pediatric surgeon at a World Series game and came to trust him enough to do the surgery. He also suffered from sundowner’s syndrome where he got disoriented when he woke up in the middle of the night and fell trying to find his way.

In May 1972 Berg was staying at his sister’s house when he fell out of bed at night and hit the night stand. After four days he finally consented to go to the hospital and was diagnosed with an abdominal aortic aneurism. On May 29 he asked the nurse, “How are the Mets doing today?” and then died before he could hear the answer.

QUESTION: What contradictions do you have in your personality that make you seem like two different people? How does that impact your life?

©2011 Debbie Foulkes All Rights Reserved

Sources:

Dawidoff, Nicholas, The Catcher Was a Spy; The Mysterious Life of Moe Berg. New York: Pantheon Books, 1994.

Kaufman, Louis; Fitzgerald, Barbara; Sewell, Tom, Moe Berg, Athlete, Scholar, Spy. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1974.

http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/biography/MBerg.html